Ciberseguridad en #espacio: cómo se está enfrentando Thales a los desafíos que están por llegar

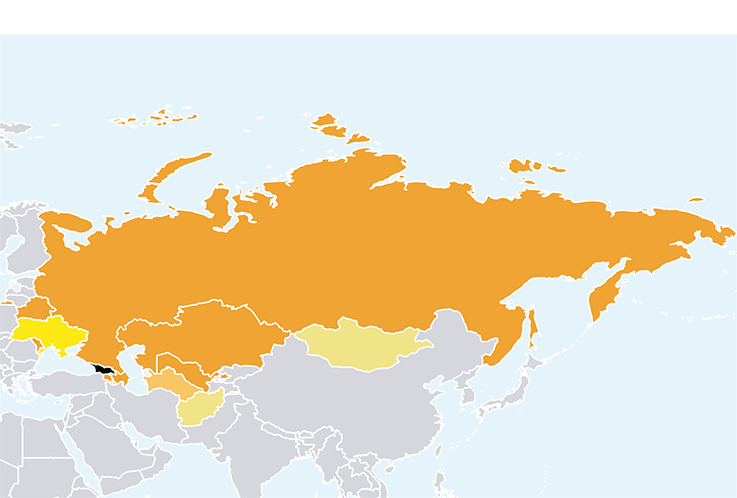

> Countries List :

Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Russia, Russian Federation, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan

Contextual analysis of CIS and Geocyber risks

On 8 December 1991, just before the USSR officially collapsed, Russia, Ukraine and Belarus signed the Minsk Treaty. This treaty established the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), which was intended to guarantee a form of multilateral consistency between the former Soviet republics, despite the overall disintegration.

On 21 December, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Moldova and Tajikistan joined the CIS. Two years later, in 1993, Georgia joined the group. It should be noted that the Baltic States, former soviet socialist republics, never joined the CIS. This organisation, built on the historic foundations of the Eastern Bloc, is made up of a set of complex, intertwined dynamics, a Soviet Union centred on Moscow and the influences of new powers in a multipolar world. This confrontation leads to the emergence of regional tensions that justify the use of cyber as a vector of influence.

Main types of Attackers

Adversary types

Top 3 Attacked sectors

- Aviation

- Communication

- Information Technology

Commonwealth of Independant States News

See moreThe Caucasus is a strategic zone in several respects. First, geographically, it serves as a buffer zone between two continents: Europe and Asia. North of the Greater Caucasus mountain range, on the Georgian and Azerbaijani borders, lies Russia, the former heart of the Soviet Union. To the south is Turkey, with its Sunni nationalist culture, and Iran, which has a Shiite Islamic culture. The three countries are geographically intertwined and bordered to the east by the Caspian Sea and the west by the Black Sea. This particular geography and topography makes the Caucasus a narrow corridor and a crossroads of cultures and identities. This crossroads is also strategic and lead certain nearby powers — such as the European Union (with NATO), Turkey, Iran and Russia — to assert their influence in the region

_SEPARATISM, NATIONALISM AND JIHADISM IN GEORGIA

After the fall of the USSR, many internal conflicts broke out. In Georgia, a civil war (1991-1993) pitted the secessionist provinces of Abkhazia and South Ossetia against the central government in Tbilisi1 . Geographically, the Caucasus extends into Russian territory, with the North Caucasus. It was in the North Caucasus that the First Chechen War erupted in 1994. This conflict — as in Abkhazia and South Ossetia — was the scene of confrontation between independence movements and a former Soviet republic, in this case Russia. The regional consequences of the Russo-Chechen conflicts are significant and make terrorism even more entrenched. For example, the Pankisi Gorge crisis from 2002 to 2003 saw Georgia clash with Chechen rebels and members of Al-Qaeda. The 2000’s were also marked by the appearance of colour revolutions in former Soviet republics, in Georgia in 2003 (Rose Revolution), in Ukraine in 2004 (Orange Revolution) and in Belarus in 2005 (Jeans Revolution). Characterized by popular, peaceful demonstrations, these revolutions highlight the confrontation between Western influence and Russia’s desire to control its near abroad. The democratic aspirations of the people and the spectre of the emergence of pro-Western civil societies in the region motivate Russian interference, particularly through disinformation campaigns as a part of a more global hybrid warfare strategy.

In 2008, a war broke out between Georgia and South Ossetia, supported by Russia, Abkhazia and the CIS armed forces. This conflict, which Georgia lost, allowed to leave the CIS. This conflict signals the resurgence of Moscow’s influence, which is posing as the protector of secessions.

In 2007 and 2008, around the time of the Russo-Georgian War and the widespread attacks in Estonia, the ATK5 group (APT28) really began to structure its attack campaigns. From 2007 to 2014, ATK5 (APT28) massively targeted Georgian government agencies, including the Ministry of the Interior and Ministry of Defence, as well as civilians. The ATK14 group (BlackEnergy) also launched massive DDoS attacks against Georgia and later began to target Estonia as well. The source code of the malware was sold at that time, which increased the number of attacks on Georgia. From 2011 to 2013, another ATK14 malware called Potao was used to target Armenia and Georgia. In late 2013, it began to be deployed in Ukraine, with several samples used to target this country. From September 2014, the victims of this malware included Ukrainian government agencies and the armed forces.

In spring 2010, the ATK7 group (APT10) conducted actions across the entire Caucasus and Central Asia, with continued campaigns using PinchDuke against Turkey and Georgia as well as numerous campaigns against other members of the Commonwealth of Independent States, such as Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan. This same malware was identified in Chechnya in 2008. In 2015, ATK7 (APT29) also targeted Georgian entities with the CosmicDuke malware and a file attachment with a name in Georgian that translates “NATO consolidates control of Black Sea. docx”.

_CONFLICT BETWEEN ARMENIA AND AZERBAIJAN LINKED TO THE QUESTION OF NAGORNO-KARABAKH

The path to the independence of Armenia from Azerbaijan was made in the throes of a war (1988-1994) between these two former Soviet republics. In 2020, a second war broke out between Nagorno-Karabakh, supported by Armenia, and Azerbaijan and the Syrian National Army, backed by Turkey. In November 2020, a ceasefire was jointly announced by the belligerents. Azerbaijan regained possession of the Agdam, Kalbajar and Lachin districts. Tensions are still extremely high in the region and animosity between Armenia and Azerbaijan remains significant. The 2020 conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh was also the theatre of a lot of cyber activity. The ATK116 group (Inception, Cloud Atlas) was active in October and November 2020 with an espionage campaign based on use of an article entitled: “Armenia transfers YPG/PKK terrorists to occupied area to train militias against Azerbaijan”. Both sides were targeted in this campaign. Threat actors also conducted attacks against Armenian targets using Zero Days via Chrome and Internet Explorer. Azerbaijan was targeted by the ATK178 and ATK228 groups and the PoetRAT malware. The targets were highly specific and appeared to be mainly Azerbaijani public and private sector organisations, especially ICS (Import Control System) and SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) systems in the energy sector. The number and variety of tools they used indicate that the attacks were carefully planned. The ATK228 group’s main objective was to compromise the wind power companies that produce Azerbaijan’s electricity. On 5 August 2020, ATK5 (APT28) also launched an attack campaign using the Zebrocy malware against several NATO member governments, Middle Eastern governments and the Azerbaijan government, which cooperates with NATO. This attack campaign came just days after the clashes between Azerbaijan and Armenia and less than two months before the began on 27 September.

_CENTRAL ASIA, WITNESS TO RECONFIGURATIONS OF POWER UNDER CHINESE INFLUENCE

The Central Asia region partly corresponds to historic Turkestan. This region, which is as large as the European Union, is made up of five countries: Kazakhstan in the north, Kyrgyzstan in the east, Tajikistan in the southeast, Turkmenistan in the southwest and Uzbekistan, which is landlocked between these four countries. The Great Steppe covers the north and the South mainly correspond to desert regions. These five countries, which became independent from the Soviet Union in 1991, are surrounded by Russia to the north and west, China to the east and Iran to the south. Chinese influence in the region was strengthened with the launch in the fall of 2013 of the «Silk Road Economic Belt.» It is one of the priorities set by the Chinese government for the years ahead. An extensive network of transport, pipeline and telecommunication infrastructure will form the physical skeleton of a future Eurasian “economic corridor”. This network will link China to Western Europe by land via Central Asia, Asia Minor, the Persian Gulf, the Caucasus and the Balkans. It will also link them by sea via the South China Sea, the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf through to the Mediterranean.

The $50 billion Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the $40 billion Silk Road Fund were set up by Xi Jinping to inject investment into regional infrastructure. Despite the altruistic rhetoric, Beijing is responding to national priorities and serving primarily Chinese economic, political and strategic interests. While based on the historic aura of the ancient road that linked the Chinese and Roman empires, the objectives of these “new silk roads” are adapted to serve contemporary geopolitical needs. Central Asia is a key part of the original New Silk Roads project, which aimed to promote the construction of transport infrastructure between China and Europe. Xi Jinping’s speech announcing the launch of the Silk Road Economic Belt was made in Astana (renamed Nur-Sultan on 23 March 2019), Kazakhstan. The imagery of the Silk Roads is especially resonant in this part of the world, which was at the heart of the trade flows between Europe, the Middle East and the Chinese Empire prior to the 15th century. Of the six “economic corridors” in the new Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), two directly concern Central Asia: the New Eurasian Land Bridge (China, Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, Poland, Germany) and the China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor (China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Iran, Turkey).

In spite of having become the first trading partner for central Asia countries, China’s interest in its neighbouring region to the west is not only based on an economic vision. For the Chinese central government, helping stabilise and develop the countries on its western front is a way to avoid instability at the gates of its western Xinjiang region. This region, considered unstable by Beijing, is mainly populated by ethnic Uyghurs. Security cooperation between China and Central Asia is largely centred around the Uyghur question and the fight against the “three scourges” identified by the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO): terrorism, separatism and religious extremism. In the years ahead, Russia’s reactions to China’s growing presence in its historic area of influence will be closely watched. For Russia, the BRI certainly comes with advantages, such as investment capacities that it cannot offer its partners and that will help improve infrastructures and make trade within the EAEU more seamless. Launched in 2015, it does not challenge Russia’s monopoly on political-security issues in Central Asia — at least for now — and it supports institutional recognition of the EAEU as a credible and legitimate regional organisation3. Nonetheless, China’s security presence could be strengthened in the medium or long term with the expansion of Chinese economic interests in the zone, as can be seen in Tajikistan.

_LOOKING AT THE MAJOR ATTACKERS WHO HAVE TARGETED THE REGION, WE QUICKLY SEE THAT THE GEOPOLITICAL CONTEXT HAS A SIGNIFICANT IMPACT ON THE NATURE AND STRUCTURE OF THE CYBERTHREAT.

The cyber continuity of the Chinese Silk Road initiative is rendered essential by the need to secure sea and land routes. Among the 360 cyberattack campaigns observed since the birth of the project, one can notice the presence of high-intensity actors with allegedly close ties to Chinese authorities. The ATK15 (Emissary Panda) group launched campaigns between fall 2017 and March 2018 targeting a Central Asian data center. The use of a compromised router (RouterOS Mikrokit) allowed the attacker group to access government resources. While the beginnings of ATK 15 date back to 2009, its recent activity reflects China’s need to secure land and sea routes to Europe. Nevertheless, while Central Asian countries and Russia seem relatively unaffected by the massive and repeated attacks that other countries in the region (India in particular) may suffer, several indicators tend to show a reversal of this logic with the spectre of direct attacks on strategic infrastructures in Central Asia or Russia.

Other active hackers in the region such as ATK23 (Icefog) and ATK147 (Poison Carp) have targeted Uyghur and Tibetan minorities in particular.

We have observed that the countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States, which were formerly Soviet republics5, share two main characteristics. First, they have a high risk of internal instability (within each country and across the broader regions), notably due to the emergence of separatist movements in the Caucasus. In addition, they are strategically important, because their geographic location fuel the geopolitical appetites of neighbouring powers. The Caucasus is an interface between Continental Europe and East Asia. Central Asia, the heart of Eurasia, is at the crossroads of Russian, Chinese, Iranian and Western (NATO) influences. This second feature, shared by the two zones and their respective countries, is leading the world’s major powers to project their influence on these territories, even if it means taking advantage of or stirring up potential internally destabilising factors.