Cybersécurité dans l'espace: comment Thales relève les défis à venir

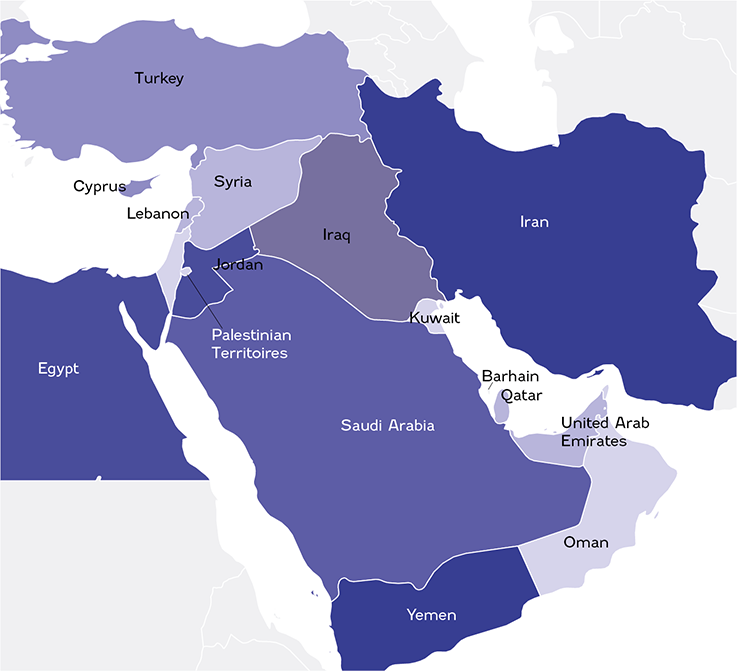

> Countries List :

Azerbaijan, Armenia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Lebanon, Kuwait, Jordan, Iraq, Israel, Syria, Qatar, Georgia, Bahrain, Palestine, Cyprus, Oman

Contextual analysis of CIS and Geocyber risks

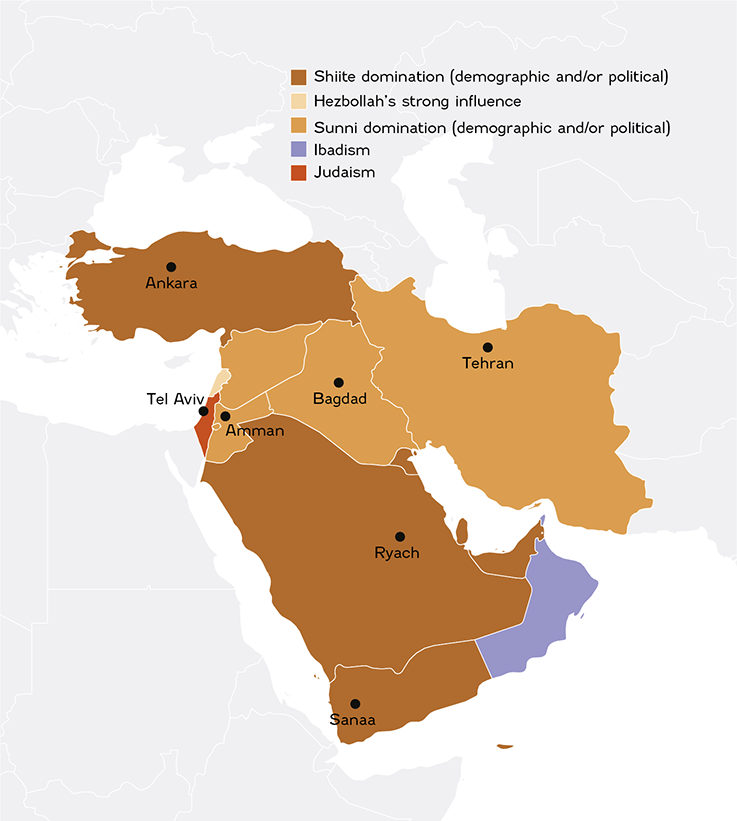

As we have seen, the Middle Eastern cyberthreat landscape is shaped by several geopolitical factors. The region is highly polarised around a fundamental divergence between Saudi Arabia and Iran. This polarisation takes the form of a subregional Cold War with a “bloc” logic that is often reduced to a simple opposition between Sunnis and Shiites, but which in reality is much more complex. These two blocs confront each other indirectly in war zones such as Syria and Yemen, as well as through militia or Islamist intermediaries. Ultimately, this complexity is transposed into cyberspace with an array of hacker groups and a sustained level of activity

Main types of Attackers

Adversary types

Top 3 Attacked sectors

- Information Technology

- Aviation

- Communication

Western Asia News

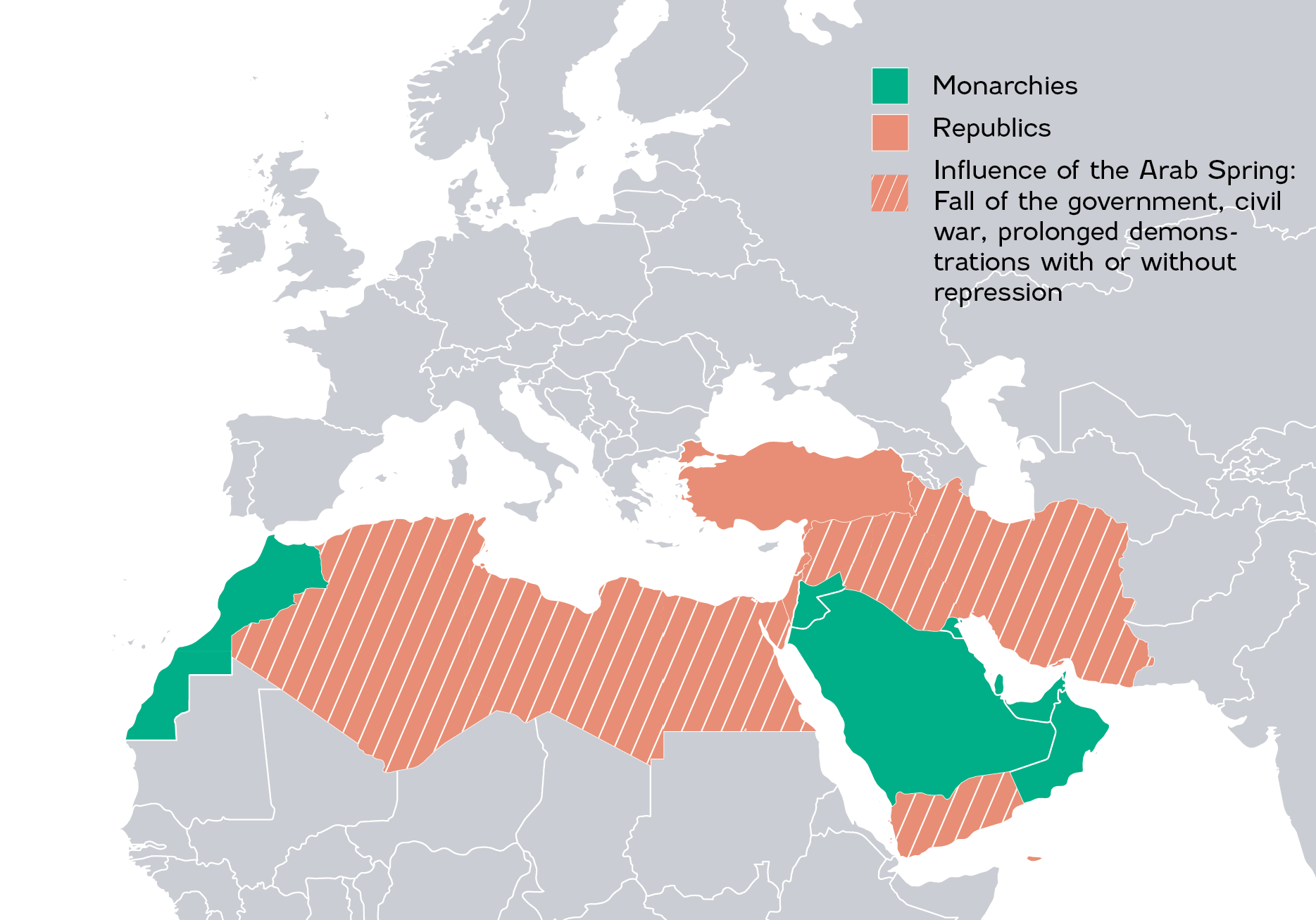

See moreIn 2011, a wave of democratic protests swept across various countries in the Arab world. From Tunisia, the desire of the North African peoples for democracy spread to Western Asia, leading to radical responses, severe repression (Kuwait) and even civil wars (Syria, Yemen). Initially, these protests took the form of peaceful demonstrations, where people expressed their disagreement with the political and institutional systems, which they deemed obsolete and corrupt. The Middle Eastern region is built around two types of political models: absolute or constitutional monarchies and republics. Many of the most important uprisings were in the Arab republics and have continued to this day in the form of civil wars, most notably in Syria and Yemen. The countries of the Arabian Peninsula, most of which are rentier states, have effectively established an unspoken social contract by offering a high standard of living for their populations.

Since the late 1980s, the Western Asia region has seen the emergence of terrorist groups advocating radical Islam and encouraging its political manifestation in the form of a violent jihad. Jihad has experienced several mutations. It was theorized as a violent struggle against the near enemy, which refers to the apostate regimes of the Middle Eastern peninsula. The first mutation appeared with Al-Qaeda. The group exported jihad across regional border and started to target the “far enemy”. Al-Qaeda first appeared in Afghanistan in 1987 and has carried out numerous terrorist acts, claiming responsibility for the attack on the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York in September 2001. The group is still active in various parts of North Africa and the Middle East, with the presence of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the Indian subcontinent (AQIS).

The second major mutation happened with Daech. The terrorist group created a horizontal structure, relying on the masses. Formed in response to America’s intervention in Afghanistan in 2003, it is mainly present in Iraq, where it has its organisational core. It is also present in North Africa, the Caucasus, Somalia, Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent. In 2014, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi proclaimed the creation of an Islamic State in Iraq. The Islamic State group took part in the Syrian conflict in 2013, fighting both Kurdish militias and Syrian regime forces, with the aim of establishing an Islamic caliphate. Building on an existing terrorist group in the region, the Al-Nusra Front, Islamic State became the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).

ON 4 APRIL 2016, THE CYBER CALIPHATE ARMY (CCA), ISIS’S MAIN HACKING UNIT, AND OTHER PRO-ISIS GROUPS LIKE THE SONS CALIPHATE ARMY (SCA) AND KALACNIKOV.TN (KTN) MERGED TO FORM THE UNITED CYBER CALIPHATE (UCC). UCC GROUPS INCLUDE

• The Cyber Caliphate, or Cyber Caliphate Army (CCA), which was created shortly after Islamic State was formed. The key person in this organisation was Junaid Hussain (Abu Hussain al-Britani), or TriCk. CCA’s most significant cyber terrorist attack was in January 2015, when the Twitter and YouTube accounts of US Central Command and later the Twitter accounts of Newsweek magazine were hacked.

• The Sons Caliphate Army (SCA) Contextual analysis of Western Asia and geocyber risks The Middle East is a region geographically and culturally diverse. It comprises the Anatolian zone with present-day Turkey, the Levant zone, which includes Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel and the Palestinian Territories, the Arabian Peninsula and the Iraq-Iran zone. Geographically, the Middle East is rich in natural resources and especially in oil and gas. Culturally, the region is home to the major monotheistic religions: Islam and its various branches (Sunnism, Shiism, etc.), Christianity (Druze, Coptic, Maronite) and Judaism. was formed in 2016 as a subgroup of the Cyber Caliphate. It is mostly known for disrupting social media traffic on Facebook and Twitter. SCA claimed to have hacked into 10,000 Facebook accounts, over 150 Facebook groups and more than 5,000 Twitter profiles.

• Kalashnikov E-Security Team was initiated in 2016. This group focuses on technology security consulting for ISIS jihadists. It has uploaded ISIS-related jihadist literature, shared posts from cyber jihadist groups, reported successful attacks on websites or Facebook pages and published various web hacking techniques. Over time, the hackers began to carry out or take part in website hacking. While we have not identified any ATK133 attacks in almost two years, it is highly likely that group members have been redeployed to new operations within other terrorist groups as a result of ISIS movements.

When Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh was forced to accept the terms of the revolutionaries under the mediation of the Gulf Monarchies in 2011, no one thought the country would collapse. However, the now former President allied with Shiite Houthi rebels, backed by Iran, in order to regain power. The country was plunged into a conflict that became international in 2015 with the intervention of a Saudi-led Arab coalition. In Syria, the democratic aspirations of 2011 quickly degenerated into a civil war sparked by the killing of children in Daraa by Bashar al-Assad’s regime. As with Yemen, the conflict became international when Islamic State got involved in 2013. What began as a national conflict quickly turned into a regional and international conflict in which Russia, Iran and Turkey have taken part. Russia and Iran have sent militias to support President Assad’s regime and its strategic interests in the region. Turkey sent in its armed forces in late 2019 after the US withdrawal from the region, officially to protect its borders and fight jihadists. Unofficially, Turkey has also been fighting the Kurds, with whom it is in conflict within its borders. This Kurdish population, present today in northern Syria but also in Turkey, Iraq and Iran, claims a territory in Syria’s north. The Kurds, a minority which has suffered for many years under the Assad clan, were spread over a territory straddling Iran, Iraq, Turkey and Syria, before the borders of these countries were defined at the end of World War II.

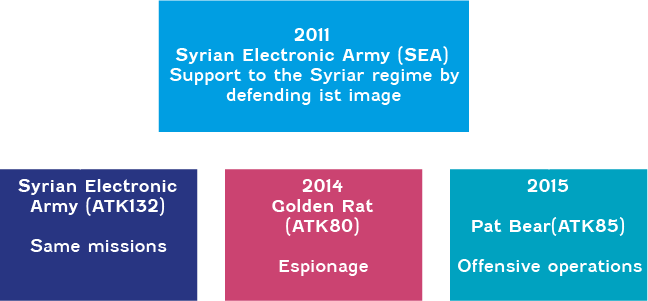

USE OF CYBER WEAPONS IN THESE CONFLICTS: THE EXAMPLE OF SYRIA

These conflicts also have a dimension that is much less reported in the media because it is less visible: cyber confrontations. In this respect, the Syrian conflict demonstrates the importance of the cyber weapon and its use by the regime of Bashar al Assad.

Firstly, the cyber tool allows the regime to carry out missions to spy on the opposition. The technique known as «man in the middle» allows the interception of communications between two stations without either operator being aware of it1 . Infowar Monitor reported in May 2011 that this type of attack was used in Syria on a secure version of Facebook, allowing the attacker to access the victim’s private conversations. Still with the objective of espionage, the Syrian government has used RATs (Remote Administration Tools), programs that allow full remote control of a computer from another device. DarkComet is a French-made RAT that has been modified to spy on Syrian revolutionary forces. Secondly, the Damascus regime uses the cyber tool to destabilize its opponents. For example, the Syrian government regularly cuts off the country’s communications to interfere with the rebels’ exchanges. In addition to cutting off the Internet and GSM networks at strategic times, it may send a large number of connection requests in order to saturate the network.

The Syrian leaders regularly mobilise hacker groups, such as ATK132 (Syrian Electronic Army) which carry out DDoS (distributed denial of service) or defacement attacks. Certain Arabic media outlets are regularly targeted by the Syrian Electronic Army (SEA). For example, the website of the Qatar-based Al Jazeera news channel was hacked by the SEA in April 2012. At the same time, the Twitter account of Al Arabiya, a Saudi Arabian television news outlet, posted bogus messages about an explosion at a Qatar gas facility, the replacement of Qatar’s Prime Minister and Foreign Affairs Minister and the arrest of the Prime Minister’s daughter in London. The SEA was almost certainly seeking to exacerbate the tensions between Qatar and Saudi Arabia in order to undermine their partnership on the Syrian issue. In January 2013, the Syrian Electronic Army announced that it had several documents detailing the role played by Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar in the Arab world for nearly two years. This information was later published on the website of Al Akhbar, a Lebanese newspaper that is reputedly pro-Hezbollah. This type of initiative is frequent and the countries targeted are always those that take an official position against Bashar al-Assad and that are accused by the Syrian government of militarily supporting the opposition.

STRUCTURE OF THE CYBERTHREAT GENERATED BY THE ASSAD REGIME

The Pat Bear group (ATK85) should not be confused with the SEA, though it is related to it. The SEA emerged in 2011 to support the Assad government in the civil war, then the regional war. Its objective was to support the President’s image and positions in a context of dissent and violence against civilians. Logically, the group uses website defacement, spam, phishing and DoS techniques, especially against opponents of the regime. In 2014, the Golden Rat group (ATK80) appeared. This group also came out of the SEA, but it does not have the same missions. It specialises in espionage and mainly directs its actions at the national level. Pat Bear emerged in 2015 with the objective of launching cyber offensive operations against the Syrian regime’s enemies, including the opposition and Islamic State.

Iran and Saudi Arabia are two major regional powers whose fundamental mutual opposition tends to shape tensions in the region. A regional Cold War type scenario has become established in the last few years around two diametrically opposed models. These two models, in the form of blocs, indirectly confront each other in the region (Syria, Yemen, etc.). This opposition is also evident in the realm of cyberthreats.

_A BIPOLAR CONFIGURATION REFLECTED IN CYBERSPACE

It appears that the Saudi bloc is partly supported by the ATK144 group (DarkMatter, Project Raven). Project Raven is a threat group that has been conducting targeted spyware attack campaignsagainst Emirati journalists, militants, activists and dissidents since at least 2012.

Circumstantial evidence suggests that there could be a link between this group and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) government. Project Raven is the offensive and operational division of the National Electronic Security Authority (NESA), the UAE equivalent of the NSA. In 2016, this project was moved to DarkMatter and began targeting America. Raven’s targets include militants in Yemen, foreign adversaries such as Iran, Qatar and Turkey, as well as specific individuals. The opposition to the Saudi bloc has been structured around groups that are certainly Iranian in origin, such as ATK40 (Oilrig), ATK26 (Rocket Kitten), ATK35 (Magnallium), ATK19 (Cutting Kitten), ATK30 (Copy Kitten), ATK51 (MuddyWater) and ATK50 (Shamoon). These groups have specialised in destructive wiper malware attacks such as Zerocleare and Shamoon. These are regularly directed against vital Saudi organisations.

THE 2017 QATAR CRISIS: A SYMPTOM OF A BIPOLAR STRUCTURE

From the 1990’s, Qatar gradually broke away from the Saudi “bloc” to demonstrate its independence and moved closer to Iran. In June 2017, after some comments allegedly made by the Emir of Qatar in which he praised Iran, Hezbollah and the Muslim Brotherhood, the petro-monarchies of the gulf severed diplomatic ties with Qatar. On 16 July 2017, the Washington Post claimed, based on sources from the US Secret Service, that the statement from the Emir originated from a computer hack perpetrated by the UAE. The objective of destabilizing the Qatari emirate and asserting Saudi power in the region has proven to be counterproductive, as witnessed by the rapprochement between Qatar and Iran. Above all, this crisis reveals the fragmentation of the Middle East around the opposition between Sunni Wahhabi Saudi Arabia and Shiite Iran. This confrontation is not simply religious, with Sunnism and Shiism, or cultural through Arab or Persian influences, but geopolitical with a desire for power and influence in the Western Asia zone. As during the Cold War, the neighbouring civil wars in Syria, Yemen and to a lesser extent Libya are turning into theatres of indirect confrontation between the two blocs.

This diversity of religions lies at the heart of the ancient problem in the city of Jerusalem, which is the cradle of the three monotheistic religions (Islam, Judaism and Christianity). Long contested because of its religious significance, Jerusalem today is the capital of both Israel and Palestine. In 1948, the declaration of independence of the Jewish State in Palestine, which then became Israel, led the member countries of the Arab League to contest and take armed action against it. Numerous confrontations between Arabs and Jews ensued in the second half of the 20th century, and countries outside the conflict took a position. What the Arab League contests is Israel’s policy of expansion, which it considers illegitimate. The Palestinians do not hesitate to protest against this policy, and various terrorist movements have been born out of this conflict. One example is Hamas, which carried out suicide attacks until 2005 and now focuses on attacks on Israeli cities. In response, Israel has stepped up its militarisation and accelerated the process of expansion into the Palestinian territories. In early 2021, clashes in Gaza, under Israeli control, flared up again like a recurring theme. They serve as a reminder that the issue of territory that divides Israel and Palestine is as contentious as ever, many decades after the conflict began. The conflict has given rise to several hacker groups, which structure their actions around this issue.

ATK89 (MOLERATS, GAZA CYBERGANG) IS A POLITICALLY MOTIVATED GROUP. IT IS ACTIVE WORLDWIDE, INCLUDING IN EUROPE AND THE UNITED STATES, BUT MAINLY IN THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA (MENA) AND PALESTINE. THE GROUP IS COMPOSED OF THREE SUBGROUPS:

• Gaza Cybergang Group 1 (aka MoleRATs). Its aim is to infect its victims with a RAT, often via text sharing platforms such as PasteBin, github.com, upload.cat and others.

• Gaza Cybergang Group 2 (aka Desert Falcons). This subgroup uses homemade malware tools and techniques. Victims are often infected by social engineering methods such as fake websites claiming to publish censored political information, spear phishing emails or social network messages.

• Gaza Cybergang Group 3 (aka Operation Parliament). It focuses on espionage and targets executive and judicial bodies around the world, but mostly in the MENA region, especially Palestine. The group has used malware with CMD/PowerShell commands for its attacks.

Each group is different in its TTPs (tactics, techniques and procedures), but they all use the same tools after taking control of their victims. ATK89 seems to still be active. In late 2020, it added two new backdoors (DropBook and SharpStage) to its arsenal as well as a downloader (MoleNet) in order to target Israel in particular. ATK66 (APT-C-23) is commonly regarded as an APT group linked to the ruling Hamas organisation in the Gaza Strip. The group was reportedly formed in 2011, but it became active in 2014, when the first attacks were detected in the wild. By examining its victims and TTPs, it is apparent that the group mainly attacks targets related to the Palestnian Authority. APT-C-23 members are native Arabic speakers in or from the Middle East. One of the most recent ATK66 campaigns began in Palestine in late 2020 and targeted people in the same region, including government officials, members of the Fatah political party, student groups and security forces.

The region is also rich in hydrocarbons (oil and uranium), which ensures that the countries of the Persian Gulf and Arabian Peninsula benefit from significant financial returns. As a result, these countries satisfy the primary needs of their populations, such as medical care and social infrastructure (universities, etc.) and even exempt them from taxes.

Hydrocarbons are like a drug in the Middle East. Internally, the rentier countries enjoy the satisfaction of substantial and continuous income streams. However, this income is dependent on world prices, which can create a kind of “withdrawal” effect. This serves as a geopolitical lever in the region, especially in the context of the Iran-Saudi Arabia proxy conflict. Riyadh and Tehran are among the best supplied with hydrocarbons and the largest producers in the region. In 1960, they helped create the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) but soon began to display doctrinal divergences, especially at the Caracas summit in 1977, where the members aligned around Saudi Arabia’s productivist vision. Since the 1980s, Saudi Arabia has increased its production in order to bring down the price per barrel and put financial pressure on Iran. The Iranian economy, which was not diversified at the time, was quickly hit by American sanctions in the 1990s. In the future, this energy lever could pose a significant risk of geopolitical destabilisation and lead to an increase in the level of cyberthreat.

As we have seen, the Middle Eastern cyberthreat landscape is shaped by several geopolitical factors. The region is highly polarised around a fundamental divergence between Saudi Arabia and Iran. This polarisation takes the form of a subregional Cold War with a “bloc” logic that is often reduced to a simple opposition between Sunnis and Shiites, but which in reality is much more complex. These two blocs confront each other indirectly in war zones such as Syria and Yemen, as well as through militia or Islamist intermediaries. Ultimately, this complexity is transposed into cyberspace with an array of hacker groups and a sustained level of activity.